Army wife, author, and territorial era Arizonan Martha Summerhayes detailed the many challenges of nineteenth century military life – particularly the challenges faced by military wives such as herself – in her 1908 autobiography entitled Vanished Arizona.

As March draws to a close, so too does the 27th annual national observation of Women’s History Month. Sandra Day O’Connor, the first female justice to sit on the United States Supreme Court, is frequently mentioned during the month-long celebration of women’s history and is undoubtedly Arizona’s most well-known women’s history figure. However, Arizona history is full of courageous and accomplished females, including the following women:

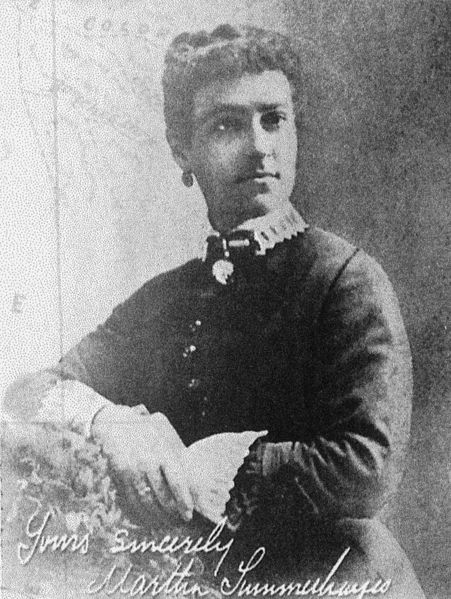

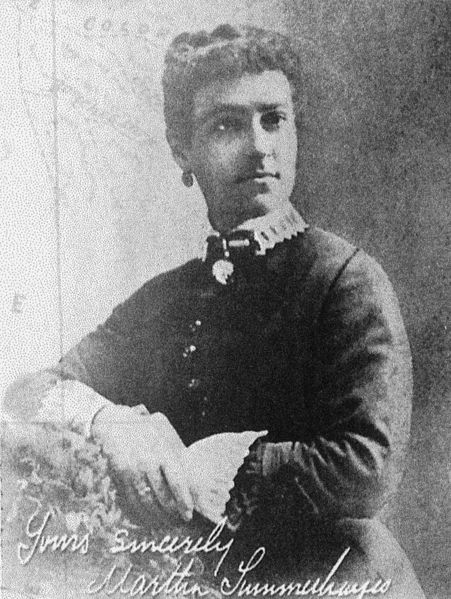

Martha Summerhayes

A nineteenth century Army wife who accompanied her husband to his assignments at military installations throughout Arizona Territory. Summerhayes documented the many challenges of frontier life in her 1908 autobiography entitled Vanished Arizona. Her book is now a valuable resource for those wishing to learn more about the role and experiences of women in territorial era Arizona military posts.

Sharlot Hall

Hall was a writer, historian, and Arizona booster. It is because of Hall’s efforts and her deep interest in our state’s history that the 1864 Old Governor’s Mansion was preserved and can be viewed at Prescott’s world-renowned Sharlot Hall Museum.

Isabella Greenway

Isabella, the widow of former Rough Rider turned copper mining executive John C. Greenway, was successful and connected in her own right. Over the course of her life, she served two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, spoke at the 1932 Democratic National Convention, owned an airline, founded Tucson’s famed Arizona Inn, and maintained a close friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt.

Nellie T. Bush

Bush was a Colorado River ferryboat captain, entrepreneur, state legislator, and, later, Parker city councilwoman who is best known for serving as the ‘Admiral’ of Arizona’s ‘Navy’ during Governor Moeur’s 1934 deployment of National Guard against California’s dam laborers. Bush’s short-lived naval force consisted of two old ferryboats that soon ran into problems and required assistance from the ‘enemy’ forces on the California side of the river, thereby ending our state’s foray into naval warfare.

Polly Rosenbaum

Rosenbaum holds the record for longest service in the Arizona legislature. She succeeded her husband in 1949 following his premature death and remained in office until January of 1995. Though her legislative service ended nearly twenty years ago, Rosenbaum is still remembered for her energy and bipartisan spirit, in addition to her work for often-overlooked rural communities throughout the state.

Additional Arizona-related women’s history facts include our state’s 1912 approval of female suffrage (eight years before women earned the right nationwide), the fact that Arizona elected women to five statewide elected offices in 1998 (Jane Dee Hull, Governor; Betsey Bayless, Secretary of State; Janet Napolitano, Attorney General; Carol Springer, State Treasurer; and Lisa Graham Keegan, Superintendent of Public Instruction), and Arizona’s nearly seventeen year run of female governors (Jane Dee Hull, Janet Napolitano, and Jan Brewer).