Cover of the 1952 edition of Oren Arnold’s Arizona Brags.

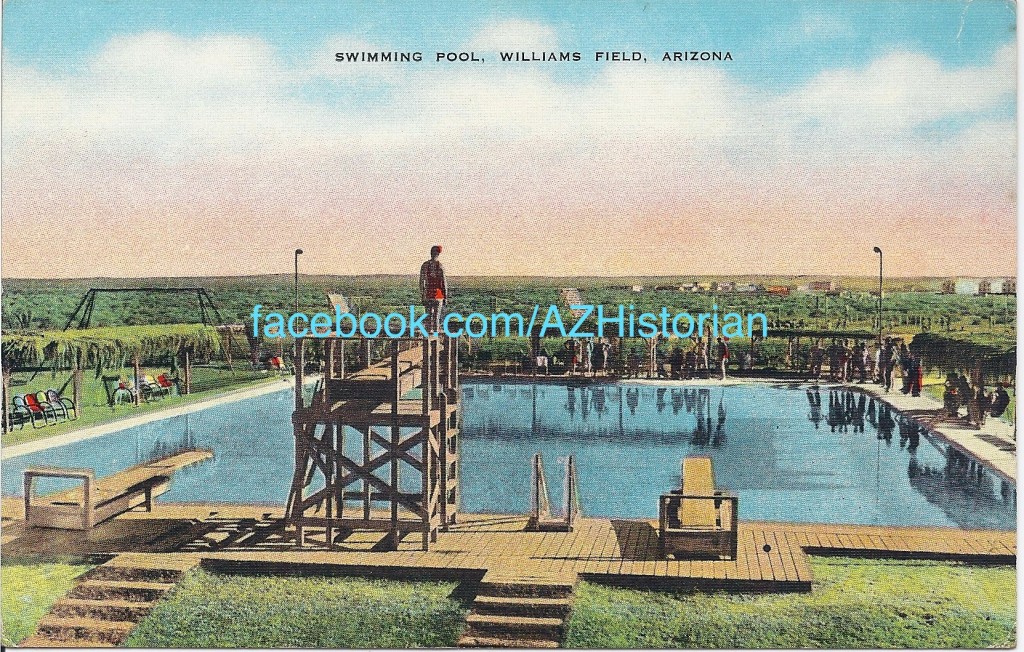

Image credit: John Larsen Southard Collection

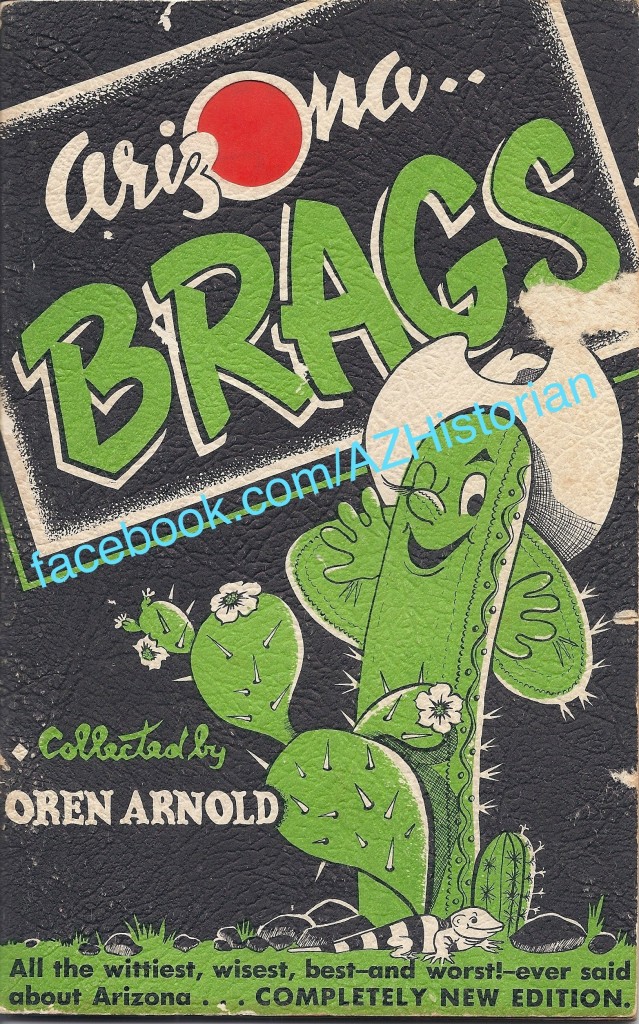

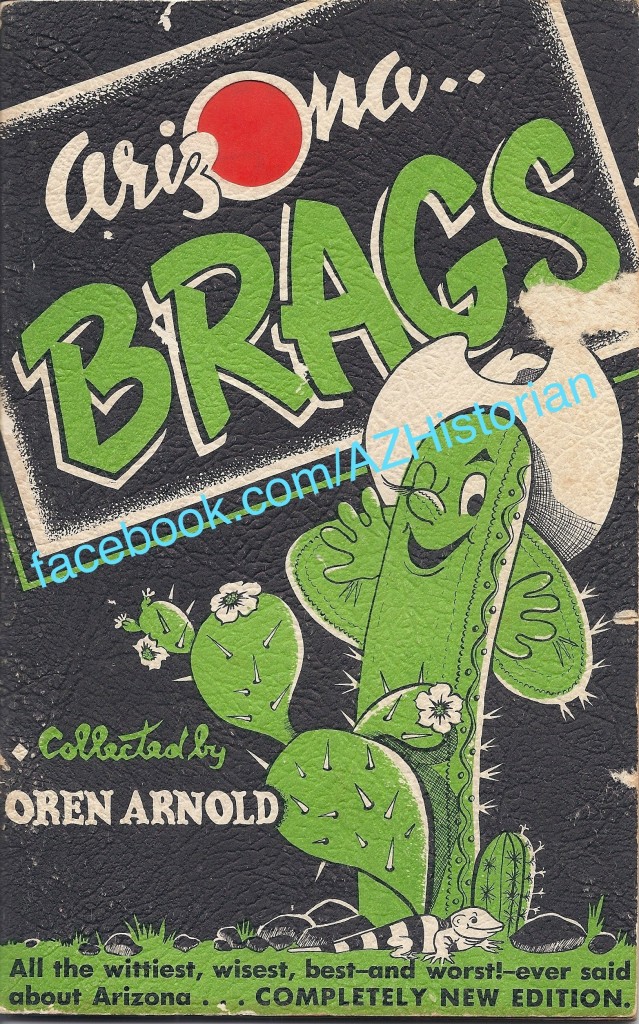

A humorous early twentieth-century postcard comparing the temperatures of Tucson and Yuma to those of Hell.

Image credit: John Larsen Southard Collection

Arizona’s climate, one of the state’s 5 Cs, is something to boast about during the winter months. Early tourism campaign slogans such as “Summer Days All Winter” were used to great effect in efforts to draw out-of-state visitors to enjoy the spectacular weather found here from November through March or, at best, April. However, the wonderful winter weather inevitably transitions to the far less desirable and often eye-popping extreme heat of an Arizona summer. These high temperatures have prompted quips such as Dick Wick Hall’s story of a seven-year-old frog who never learned to swim due to his being raised in the dry, dusty Sonoran Desert, and Mark Twain’s story of a soldier from Fort Yuma who died and “went straight to the hottest corner of perdition,” but found that after living in Yuma, he needed a blanket to live comfortably in the cooler climes of Hell.

Humorist Oren Arnold compiled a number of jokes, claims, facts, and anecdotes — many of them climate-related — for inclusion in his 1947 book entitled Arizona Brags (revised and republished in 1952). As we slide into the brutal heat of yet another summer, some of Arnold’s ‘facts’ may help to bring a smile to our collectively overheated faces. Among other assertions, some believable and some outlandish, Arnold’s book jokingly claims:

— “The devil himself carries a palm leaf fan in Arizona.”

— “It never rains. Only reason an Arizona home has a roof is to have a place to put the TV [antenna].”

— “It stays so dry in western Arizona the fish kick up clouds of dust as they cruise the Colorado River.”

— “Any Phoenix doctor says that his medical practice is twice as hard as that of doctors in any other part of the nation. He can’t tell his patients to go to Arizona for their health.”

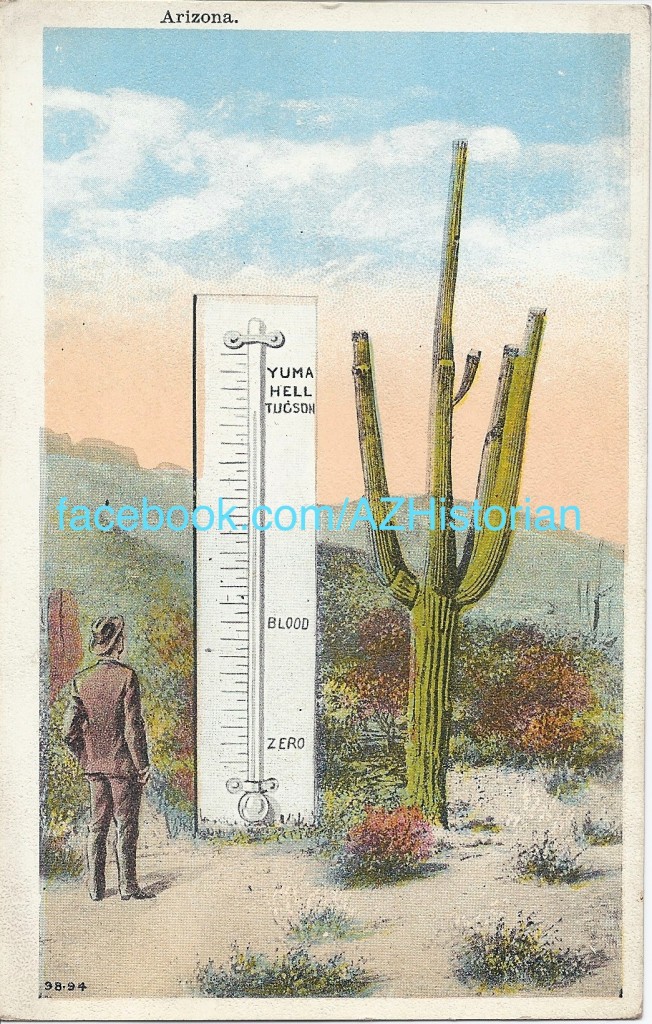

A postcard showing the swimming pool at Williams Field, later to be known as Williams Air Force Base. While airmen such as the Milwaukee native native referenced in the above joke might have initially found the Sonoran Desert climate to be unbearable, the large numbers of World War II veterans who chose to relocate to the Valley in the post-war period indicate that one need not be a native to “stand the weather.”

Image credit: John Larsen Southard Collection

— “A young GI from Milwaukee was sweating out his first summer at Williams Air Force Base near Phoenix. A native Arizonan explained that a man had to be born and reared here to stand the weather. ‘What!’ exclaimed the soldier. ‘You mean folks live here when there ain’t no war?’”

— “It gets so dry in Arizona the jackrabbits carry canteens and the trees chase after dogs. Only mud is the kind the politicians sling. Rivers are just lines to crease a map, and to furnish Arizona cattle a dry, sandy bedding ground.”

And finally, a joke related to something all Arizonans have been guilty of at one time or another…

— “A citizen of Phoenix died and, of course, went down below. The devil greeted him and was showing him around the place. The ex-Phoenician kept mopping his brow. Finally he spoke up.

‘Gosh, it certainly is hot down here.’

‘Yes, it is,’ Satan nodded. ‘But it’s not humid, it’s a healthful, dry heat.’

‘Phooey!’ scoffed the Arizonan. ‘I’ve heard that old guff before.’

‘Oh sure you have,’ Satan smiled affably. ‘Fact is, you told it. That’s why you’re here.’”