Photo of a Sun City Leisure Lawn included in a March 1963 National Geographic article on Arizona.

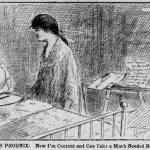

Headline and photo from a February 23rd, 1963 Arizona Republic article on Leisure Lawns.

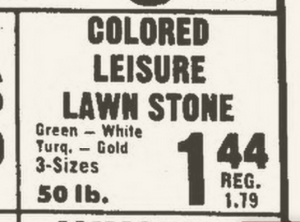

A 1968 Arizona Republic ad for Leisure Lawn Stones.

Bermuda grass is considered a weed in most parts of the nation. In many Arizona communities, however, a patch of bermuda is not an unsightly blight on the landscape, but is instead thought of as a ‘lawn.’ Of course, the blistering heat of an Arizona summer often proves overwhelming for even the best maintained Sonoran Desert-variety lawns, leading some to seek an alternative to the cost and labor required to maintain grass in the desert. Enter the “Leisure Lawn.”

A 1972 Arizona Republic ad for Leisure Lawn Stones.

Arizonans who have driven through Sun City, Mesa’s Leisure World, Pima County’s Green Valley, or any number of mobile home parks throughout the Phoenix, Tucson, and Yuma metropolitan areas have likely seen many such lawns, which appear verdant year-round regardless of temperature or rainfall levels. The rich green color of these lawns is not the result of a Space Age turf-greening technology developed at one of the state’s universities. Rather, it is a material no more technologically advanced than the pet rock was biologically innovative — painted rocks.

A 1973 Arizona Republic ad for Leisure Lawn Stones.

Leisure Lawns came about as a product intended to serve as a low-cost, no maintenance lawn that that could withstand the brutal Arizona sun, thrive in times of drought, and render lawn mowers obsolete. Though now little more than a kitschy relic of Arizona’s mid-century retiree influx, Leisure Lawns were once quite popular throughout the warmer regions of the Grand Canyon State.

A 1976 Arizona Republic ad for Leisure Lawn Stones.

The green rock fad, something likely incomprehensible to residents of more temperate climes, was touted in a February 23rd, 1963 Arizona Republic article as a choice that allows “retired couples who prefer hobbies to hoeing” to “have an at-ease lawn, thanks to colored gravel,” and won notice in National Geographic’s March 1963 story entitled “Arizona: Booming Youngster of the West.” However, just as tail fins, hula hoops, and drive-in theaters have faded from the scene, so too has the Leisure Lawn. A 2011 Arizona Republic article lamenting the demise of the water-conscious landscaping option detailed the growing rarity of this once-common sight, bringing renewed — albeit brief — attention to green rock landscaping. In this age of xeriscaping, might Leisure Lawns be poised for a comeback? Just imagine the Phoenix Open played on a course comprised of green-painted rocks…