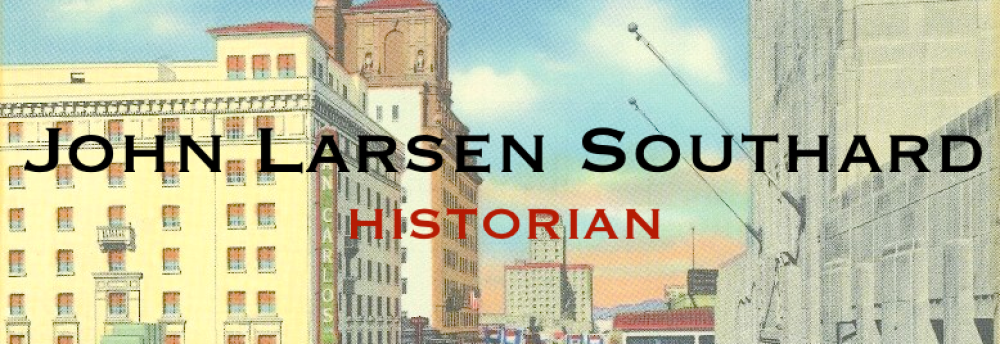

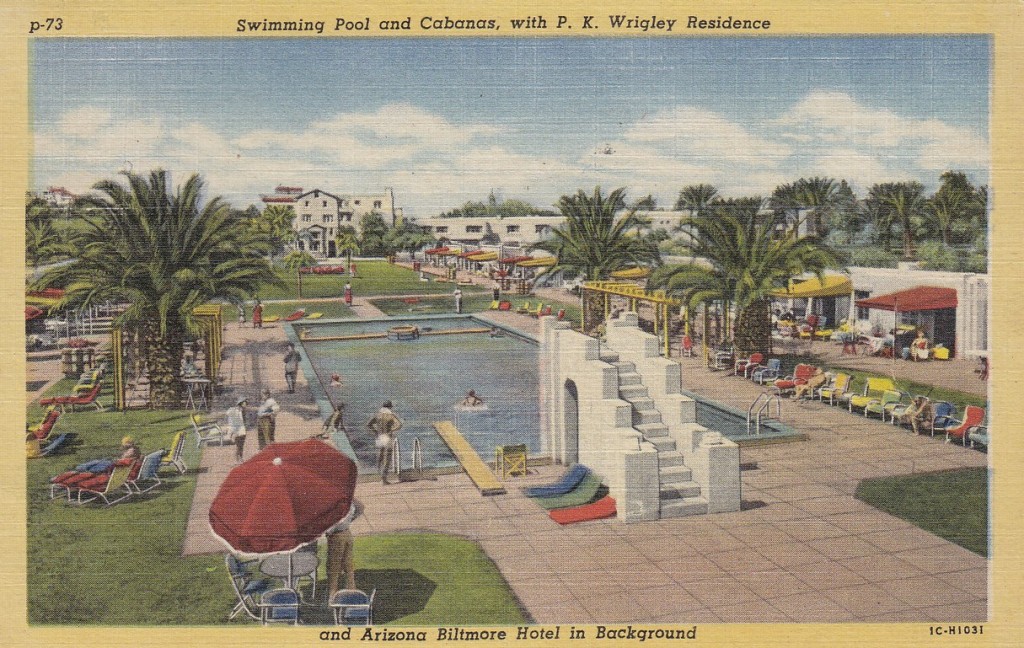

An early-twentieth century hand colored postcard depicting a seemingly idyllic scene on the grounds of the Phoenix asylum.

Image credit: Author’s collection.

Tucsonans Go Crazy Over Phoenix’s Insane Asylum

March of 1885 was a momentous month for Arizona’s Thirteenth Territorial Legislature, a group known to history as the “Thieving Thirteenth.” The legislative body described in a March 28th, 1885 Arizona Weekly Citizen article as “not excelled in its provisions for a first-class steal from the Territory” passed bills authorizing the establishment of a teachers college in the then small town of Tempe and a university in Tucson, the most populous city in Arizona at the time. The teachers college, initially named Tempe Normal School but now known as Arizona State University, received an appropriation of $5,000 while Tucson’s university brought that city $25,000 in funding. Nonetheless, Tucsonans were both disappointed with and outraged by the gift the territory’s solons bestowed upon them. In place of showing gratitude for his town’s new institution of higher education, the editor of a Tucson paper decried the Phoenix area’s capture of “the plum of the legislature pie” with “emoluments [amounting] to almost half a million” and presciently predicted that C. C. Stephens, one of Tucson’s legislators, “will be insulted when he returns.”

Why were Tucsonans so upset with their haul from the Thieving Thirteenth? Because their prize proved to be a university that the city was said to “not care a fig about.” Instead, residents of the Old Pueblo coveted Phoenix’s big score – the territorial insane asylum now known as the Arizona State Hospital and the $100,000 appropriation associated with that facility. Angry about losing this well-funded institution to the relatively new and still rather small city of Phoenix, Tucson newspaper editors wrote scathing pieces belittling the future capital city and cursing its good fortune. Southern Arizona journalists continued to attack Phoenix’s victory for several years after the 1885 legislative session adjourned sine die, as demonstrated by an August 3rd, 1889 Arizona Sentinel article expressing concern that “the Great Salt River [V]alley” was “no place for the insane” due to its stifling heat. While calling attention to “the poor suffering humanity that [sweltered] within” the asylum, the piece altogether disregarded the well-being of sane Phoenicians and conveniently overlooked Tucson’s high summer temperatures.

In the end, however, Tucsonans came to love their university, which now boasts enrollment of more than 40,000 students and an annual budget exceeding $450,000,000. With approximately 60,000 students attending courses in Tempe alone, the once-modest Normal School now lays claim to the title of largest public university campus in the United States. Phoenix’s asylum, the so-called plum of the 1885 legislative session, is now largely unknown to most Arizonans and operates on a budget of just $30,000,000 – far smaller than that of the University of Arizona. So, it seems that the much maligned C. C. Stephens has been vindicated – something likely to be deemed crazy by a Tucsonan of 1885.