Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium

Credit: Wikipedia

ASU’s Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium was dedicated on September 16th, 1964. Though many now associate the name Gammage with only the performing arts venue or attorney Grady Gammage, Jr., the auditorium stands as a monument to a man who greatly impacted Arizona’s development – Dr. Grady Gammage, Sr. Here are a handful of Dr.Gammage’s many notable accomplishments:

– Arrived in Arizona just months after statehood. Though nearly broke when he set foot on Arizona soil, he managed to earn a degree from the University of Arizona in 1916.

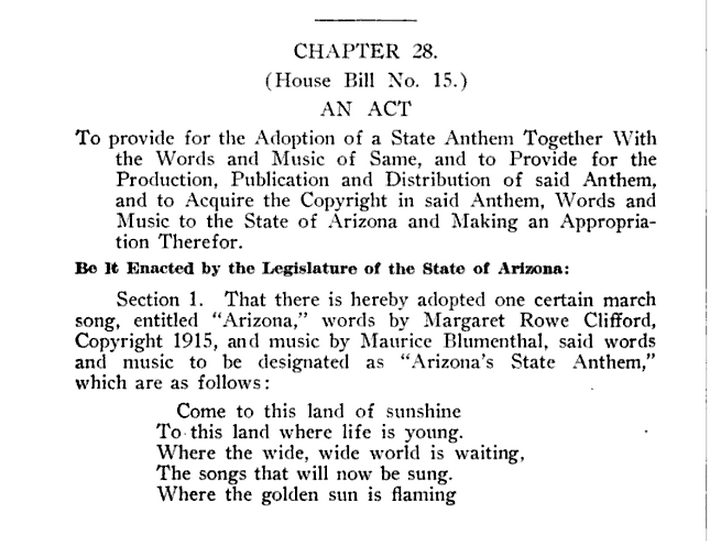

– Led a successful 1916 initiative campaign expanding Arizona’s 1914 Prohibition law.

– Served as a high school principal in Winslow, AZ.

– Assumed the presidency of the Flagstaff teachers college, now Northern Arizona University, in 1926. Led the institution through the early years of the Great Depression.

– Named president of the Tempe teachers college, now Arizona State University, in 1933. Briefly served as president of both the Flagstaff and Tempe colleges.

A bust of Frank Lloyd Wright on display at Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium

– Enlarged the Tempe campus, substantially grew enrollment figures, and presided over the creation of many academic programs critical to the Valley’s incredible post-World War II growth.

– Oversaw the effort to pass Proposition 200, a 1958 ballot initiative that elevated Arizona State to full university status.

– Championed the idea of building the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed auditorium that bears his name.

Should you wish to learn more about the auditorium or take part in its anniversary celebration, please consider attending an open house scheduled for September 28th, 2014. For more information, see: http://asugammage.com/openhouse