- Barry Goldwater’s birth certificate lists a New Year’s Day arrival date. However, the document is suspect due to it having been issued thirty-three years after the event and certifying a date of birth without citing any documentation dating from the birth year. Instead, the oldest listed supporting evidence dates to just 1936.

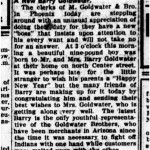

- January 2nd, 1909 Arizona Gazette article announcing the birth of a “new ‘boss'” for “the clerks of M. Goldwater & Bro. in Phoenix.” The Gazette was an evening paper, meaning that the line regarding Goldwater having been born “at 3 o’clock this morning” refers to the early hours of January 2nd, not New Year’s Day.

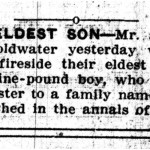

- The Arizona Republican announced Barry Goldwater’s likely January 2nd birth on January 3rd, 1909 by informing readers that Mr. and Mrs. Goldwater “yesterday welcomed to their fireside their eldest son and heir.”

- Goldwater stated his birthdate as January 1st, 1909. The Senator’s assertion, whether accurate or not, is now memorialized in bronze on his Paradise Valley grave marker.

Today is the 115th anniversary of Barry Goldwater’s birth – or is it?

Senator Goldwater’s Birthday – His Real Birthday – Is Up for Debate

2008 is not the first year that a birth certificate has factored into a presidential election. Both of Arizona’s presidential nominees faced questions surrounding their birthplaces. 1964 GOP nominee Barry Goldwater contended with a handful of people challenging his candidacy due to his birth in pre-statehood Arizona, although few seriously believed birth in a U.S. territory would preclude someone from serving in the Oval Office. 2008 Republican nominee John McCain’s 1936 Panama Canal Zone birth also brought some degree of Constitutional skepticism, although legal scholars quickly dismissed such concerns. However, a more interesting question regarding Senator Goldwater’s birth remains unanswered, and is unlikely to ever be answered definitively.

Goldwater long claimed January 1st, 1909 as his date of birth. New Year’s Day 1909 is the date listed on his Arizona birth certificate, in his official United States Senate online biography, in his 1988 autobiography entitled Goldwater (page 37), and cast in bronze on his Paradise Valley grave marker. Despite the many official references to a January 1st birth, Senator Goldwater was likely born on January 2nd, 1909 – one day later than his oft-cited New Year’s Day arrival.

Having been born at the long-since demolished Goldwater home at 710 North Center Street (now Central Avenue) in Phoenix, Mr. Conservative’s birth was not memorialized in hospital records. In addition to the lack of hospital documentation, the Senator was not issued a birth certificate in 1909. Instead, he requested that the state issue formal documentation of his birth in 1942, or thirty-three years after the event, thereby greatly reducing the document’s value as a record of Goldwater’s birthdate. Significant Goldwater family events further complicate the mystery of the Senator’s true birthdate.

Baron and Josephine Goldwater, Barry’s parents, were married on January 1st, 1907, or two years prior to the birthdate claimed by Senator Goldwater. Joanne Goldwater, Barry’s first child, was born on January 1st, 1936 – twenty-seven years after Barry Goldwater’s supposed New Year’s Day arrival. Therefore, when Goldwater requested a birth certificate in 1942, a combination of family lore and New Year’s Day family milestones may have prompted the future statesman to give January 1st as his birthdate. By the time the state issued Goldwater a birth certificate, January 1st had already been listed as his date of birth on his Equitable Life Assurance Society policy, application for military pilot training, and his daughter’s birth record, all of which were submitted with his birth certificate application as proof of a January 1st, 1909 birthdate. Period newspaper coverage of the Goldwater family scion’s birth, however, indicates that Arizona’s favorite son was likely not born on the 1st of January, 1909.

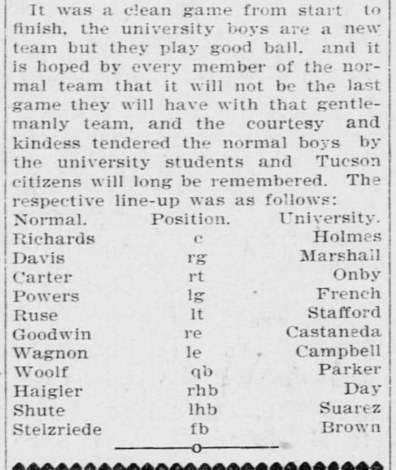

The January 2nd, 1909 evening edition of the Arizona Gazette (later the Phoenix Gazette) reported, “the clerks of M. Goldwater & Bro. in Phoenix… have a new ‘boss’,” as of “3 o’clock this morning,” serving as evidence of a January 2nd birthdate. The January 3rd, 1909 Arizona Republican (later the Arizona Republic) included an article titled “The Eldest Son,” which stated, “Mr. and Mrs. Barry Goldwater yesterday welcomed to their fireside their eldest son and heir, a nine-pound boy, who promises to add luster to a family name already distinguished in the annals of Arizona,” thus bolstering the case for a January 2nd birthdate.

So, while we may never know for sure exactly when Senator Goldwater made his debut, the strongest evidence points to January 2nd, 1909 as his true birthdate, although most official sources still reflect a New Year’s Day birth. Either way, happy birthday, Senator!