Camp Naco, an encampment of American troops along the Mexican border during the period of “border trouble,” in 1916.

Image Credit: Library of Congress

I discussed the 1934 Parker Dam controversy and the resultant birth of the ‘Arizona Navy’ with Nadine Arroyo Rodriguez of KJZZ’s “The Show” last week (clip accessible here: http://kjzz.org/content/11126/did-you-know-arizona-navy-deployed-1934). While Arizona’s short-lived two-boat naval force (or is it farce?) makes for a good story, Governor Benjamin B. Moeur’s deployment of the Arizona National Guard was a far more effective display of power. However, this border service, although notable for taking place along an interstate border, was not the first time the Guard received a call to mobilize along a border.

The Arizona National Guard, originally known as the Arizona Volunteer Infantry Regiment, or the Arizona Volunteers, was first organized in early 1865. As described in a 1955 Guard-issued history, the Volunteers were raised to “fight the Indians who were pillaging and marauding among the settlers and friendly Indian tribes” of the territory. Since that time, the Arizona National Guard has served with distinction both internationally, as was the case in World Wars I and II, and domestically.

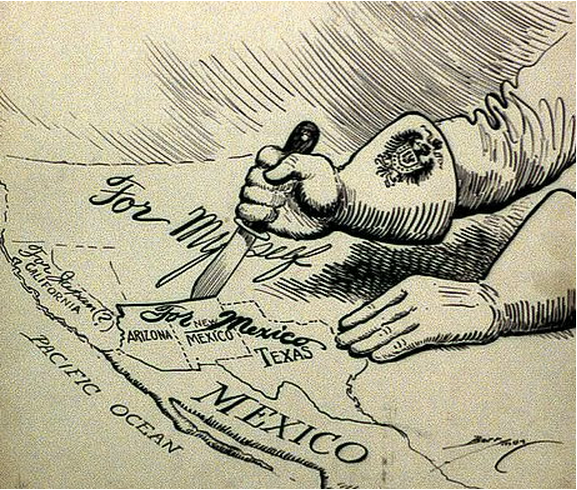

The Guard’s 1934 deployment to the California border may well be the Guard’s most-discussed domestic service, but its 1916 mobilization along the Mexican border involved risks far more dire than those faced along the banks of the Colorado River. Indeed, the decade-long Mexican Revolution that began in 1910 brought great risks to towns along the international border, as evidenced by Pancho Villa’s March 9th, 1916 raid of Columbus, New Mexico. Villa’s excursion onto American soil resulted in the death of eighteen U.S. citizens and prompted President Wilson to send General John “Black Jack” Pershing into Mexico in an unsuccessful attempt to capture or kill Villa. In response to rising tensions along the international boundary, American authorities mustered the Arizona National Guard and other border state forces into federal service. Arizona National Guard troops were federalized on May 9th, 1916 and sent to serve at Camp Harry J. Jones near Douglas and nearby Camp Naco, among other locations in the state. The Arizona National Guard’s “border trouble” era service ended with their call to train for, and eventually deploy to, France as part of America’s World War I forces.